Dr. Ilgen explores managing uncertainty in medicine

Uncertainty is a common part of clinical care, whether it’s a puzzling symptom, an evolving diagnosis, or a treatment that doesn’t go as expected. Learning to manage the unknown is an essential skill for every physician, says Dr. Jon Ilgen, who explores the topic of how to prepare trainees for clinical uncertainty in a recent New England Journal of Medicine article co-authored with Dr. Gurpreet Dhaliwal.

“Clinical work is really about managing uncertainty,” Ilgen explained. “Two people looking at the same patient may come to very different conclusions about what’s happening or what they might do.”

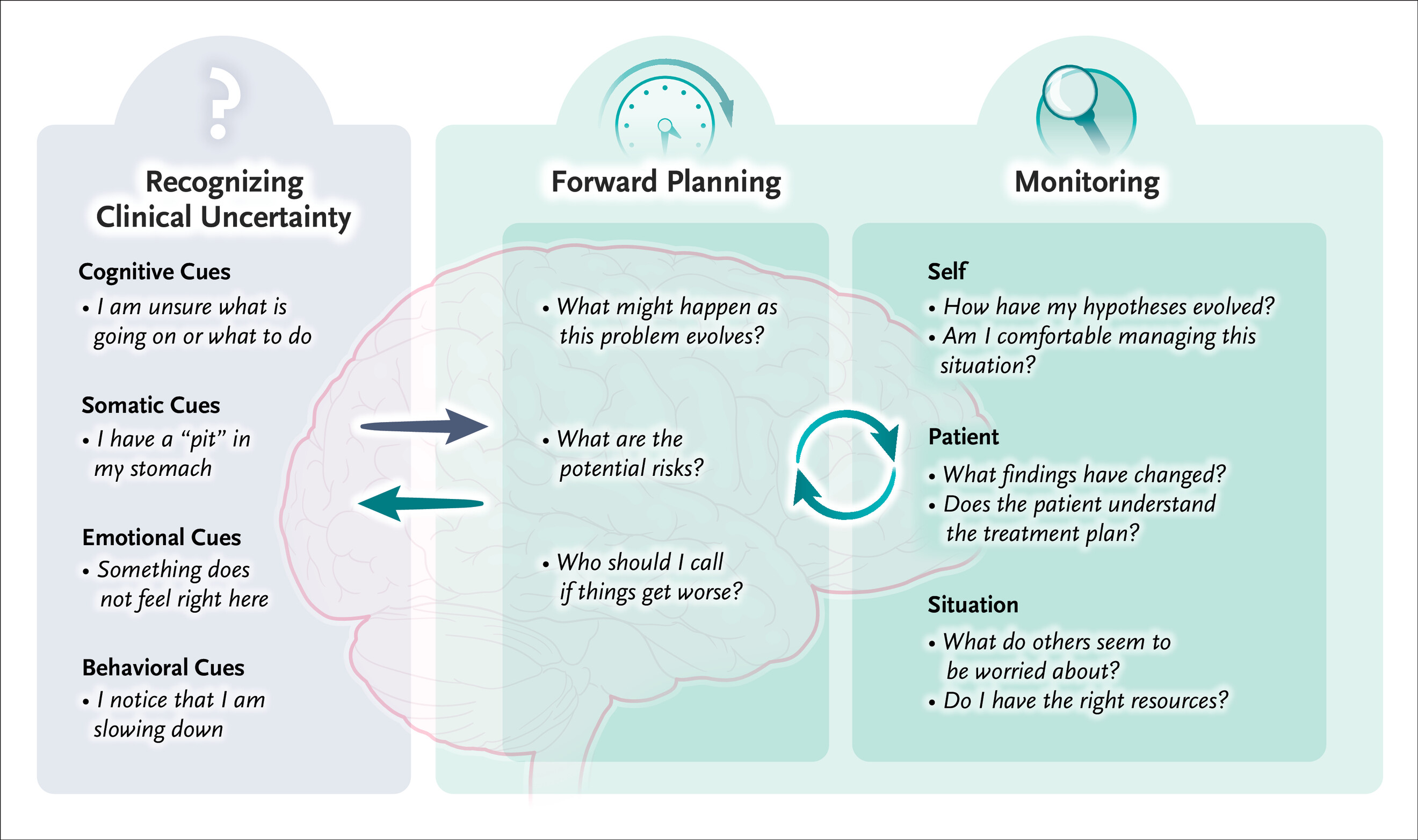

For years, research on how physicians think has focused on clinical reasoning, the process doctors use to diagnose and make decisions, according to Ilgen. However, he notes that managing uncertainty requires a complementary set of skills. The article draws from research on self-regulation, which examines how people recognize and respond to their own cues and emotions while working through problems. By connecting these ideas, Ilgen explores how self-regulation can help clinicians navigate uncertainty as it unfolds in real time.

An important aspect of navigating these experiences is monitoring, which means paying attention not just to the patient and the situation, but also to oneself. Even subtle, hard-to-define feelings can be valuable signals. Ilgen shared an analogy from one study participant: walking down a dark street and sensing that someone might be following you. You can’t see anything, but that spidey sense changes how you act. In medicine, he explained, those gut reactions can serve a similar purpose by prompting clinicians to pause, reassess, or seek input when something feels off.

He added that clinicians often push those instincts aside, thinking of themselves mainly as repositories of knowledge and experience.

“I actually think those emotions and those feelings are related to that,” Ilgen said. “We know when we’re out of bounds. We know when we’re in good control and that we’re handling something well.”

Ilgen and Dhaliwal outline several strategies that clinicians and educators can use to help trainees build confidence in managing uncertainty. These include naming uncertainty out loud, planning ahead for what might happen, and staying aware of both changes in patients, other healthcare providers, and oneself as situations evolve.

“If [a trainee] and I are caring for a patient together, we should be explicit about what we’re thinking and how we’re feeling,” he said. “That helps us notice what we might be missing and gives the trainee strategies for the future.”

The review also distinguishes between two kinds of uncertainty. Epistemic uncertainty can often be reduced with more information, such as ordering another test or seeking input from a specialist. Aleatoric uncertainty is the kind that cannot be eliminated. It reflects the natural unpredictability of medicine, like whether a patient might have an adverse reaction to a new drug. Recognizing the difference helps clinicians decide when to keep looking for answers and when to plan for different possibilities.

Ultimately, Ilgen and Dhaliwal emphasize that uncertainty is not something to be eliminated, but instead should be something that can be managed, and even embraced. Educators play an important role in helping trainees recognize uncertainty, talk about it openly, and learn practical ways to manage it in real time.

“The highly self-regulated expert is the one who knows when they know enough to act, when they’re outside their bounds, and when to get others involved,” said Ilgen.